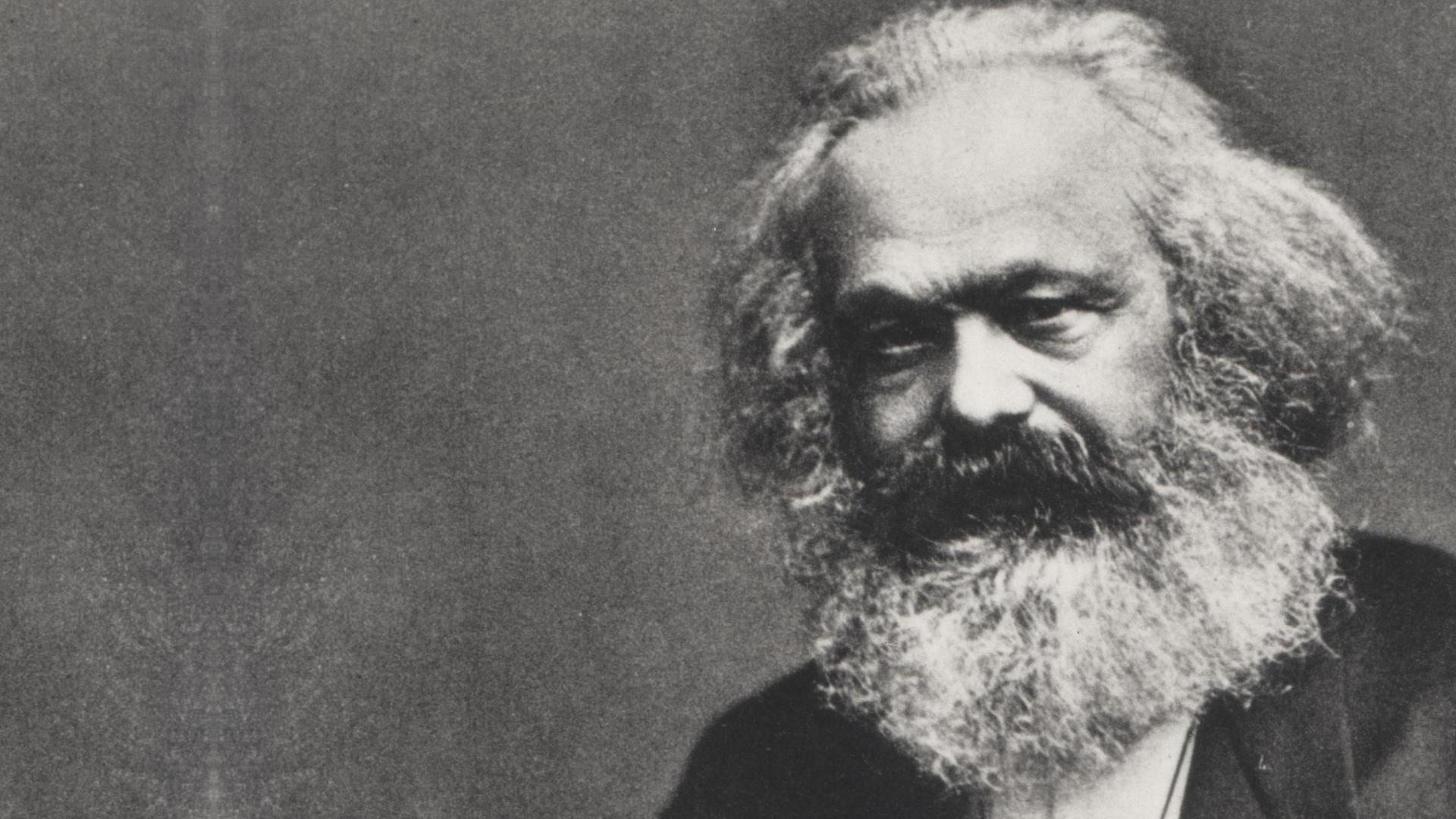

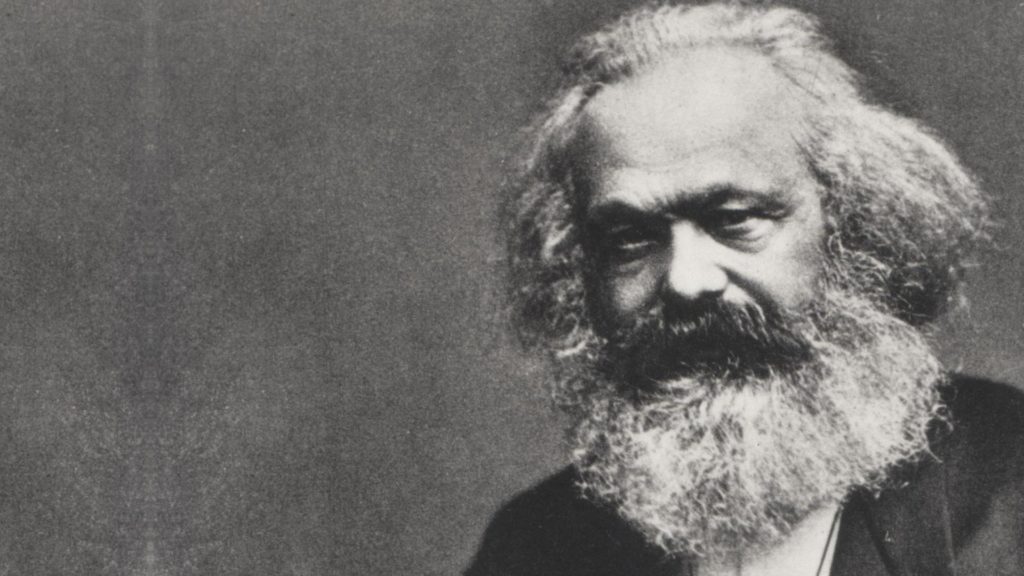

In my recent reading of Marx and Engels’s The Communist Manifesto, I was kind of surprised by the characterization made of the relationship between the employers and the workers. Marx calls the relationship exploitative multiple times throughout the work. The workers produce, and then the employer steals away the product of his or her labor. With this characterization, it is no wonder people are so against modern-day capitalist relationships. But this characterization is not the reality of the situation. It is based on loaded language and misrepresentations of the market process.

A particular passage caught my attention:

“In proportion to the bourgeoisie, i.e., capital, is developed, in the same proportion is the proletariat, the modern working class, developed–a class of laborers, who live so long as they find work, and who find work so long as their labor increases capital. The laborers, who must sell themselves piecemeal, are a commodity, like every other article of commerce, and are consequently exposed to all the vicissitudes of competition, to all the fluctuations in the market. ” (Marx par.34)

This paragraph has two core planks: the workers’ lives are dependent on capital, and the workers are owned. Marx says that the worker only lives if they can find work. One may take this as Marx saying that work is bad, but that is not what he is saying. He is saying that work is bad as long as its existence depends upon capital production. Work dependent on capital production is not a bad thing, though. An employer only will hire a worker if the hiring will bring the employer more wealth. This may seem terrible and selfish, but capital accumulation in private hands is a good thing.

Businesses will garner capital as long as they are serving consumers. The worker is part of this process. Capital accumulation for the employer means that they can go and enter into another entrepreneurial endeavor, thereby serving more consumers. Thus, the relationship between the worker and the employer being one that produces capital is good for society. Entrepreneurs and capitalists make the world a better place by serving the wants of consumers when they accumulate capital. This is not a bad thing.

But then we move on to the second plank of this passage. Marx claims that the workers “are a commodity.” On the very next page, he goes on to call the workers “slaves of the bourgeoisie class.” This is nothing more than a rhetorical trick. Any reader will want to end slavery, so when Marx calls this situation slavery it forces the reader to believe certain things without proper logical backing. The situation for the working class is not as dire as Marx makes it seem.

The relationship between the worker and the business owner is voluntary in private enterprise. The worker chooses to work for the employer for a wage they agree upon (minimum wage laws set aside). This consensually agreed upon relationship is only slavery in the furthest reaches of intellectual fantization. Any other situation would be slavery. This is the only relationship that can be outside the definition of slavery. So if this is slavery, what is freedom?

Marx believes it is slavery because the employer steals from the laborer. The employer exploits the worker and takes away the value he produces. This is also an inaccurate depiction of the relationship. The worker does not create the products he or she is employed to create from scratch. The worker creates a product using the capital goods the employer has provided them with. Thus, the employer is not stealing anything. Rather, they are paying the worker to do something with the resources they already own.

There is an institution that does steal things it had no hand at all in producing, though. It is called the state. If I were to take nature-given resources and produce a product, and then sell said product, the state would take some of my profit. This is an exploitative relationship. This is the exploitation Marx should have set his sights on.

At the same time, the employer does not buy the worker. The employer rents the labor of the worker. Buying the worker would mean they never went home to their family and they would get a one-time payment to their previous owner, not a wage paid out directly to them. Clearly, this is not the case. Workers rent out their labor voluntarily, and they are still in control of themselves.

If the employer truly did own the worker, the worker could not leave. The worker would be permanently stuck in the present job. But workers can leave if they are unhappy with the working conditions or wages. Marx talks about competition as if it a terrible fire that workers must burn in, but workers are the ones that force businesses to compete.

Competition is what brings up working conditions, pushes down prices, and keeps quality high. It is a staple of the free market and may be one of the most beneficial parts. Marx’s criticism of the relationship of the workers to the employers is misguided, and the conclusions he draws are flat out wrong. Thus, they should be entirely rejected.